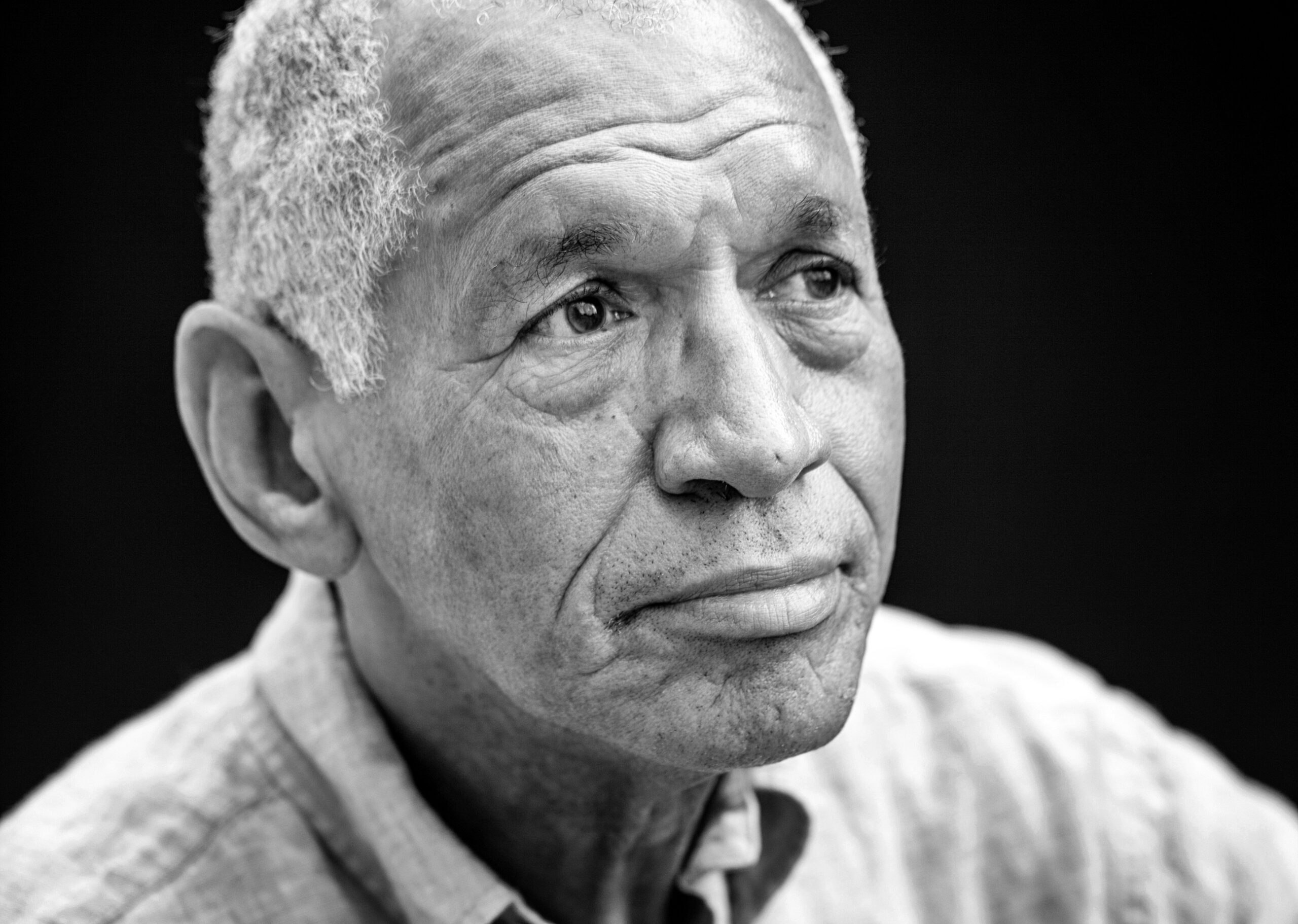

Our team is pleased to introduce Terra Alpha Voices, profiling the thought leaders who augment our investment research and contribute to our evolving impact efforts. Each subject is a visionary in their own right, supplementing Terra Alpha’s strategic vision and lending us subject matter expertise cultivated across prolific careers and diverse lived experiences. This series, created in partnership with author and photographer KK Ottesen, seeks to shed light on the persons themselves more than their illustrious careers. It is our people and their commitment who set our team apart and propel our mission forward through even the most challenging of circumstances.

Charles Bolden, Jr. served as NASA administrator, was a Major General in the U.S. Marine Corps (retired), and flew four Space Shuttle missions as an astronaut, including the mission that installed the Hubble Space Telescope and the first international mission with a Russian cosmonaut. He has been a member of Terra Alpha’s Advisory Board since June of 2019.

How did you get interested in space?

I went to Marine Corps test pilot school, and it was there that I met the late Dr. Ron McNair, one of the first Black astronauts. He asked me if I was going to apply for the [astronaut] program. I told him, “Not on your life.” He looked at me real strange, and asked me, “Why not?” I said, “They’d never pick me.” He said, “That is the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard. How do you know if you don’t ask?” And what he succeeded in doing, more than anything else, was embarrassing me. Because I had forgotten what my mom and dad told me: that you can do anything you want if you’re willing to work for it. So, when he went back home to Houston, I picked up pen and paper and wrote my application to the astronaut program.

What is it like when you first leave Earth and you’re floating and looking back?

It’s as mesmerizing and as mind-boggling as you might imagine. But what I wasn’t prepared for was the emotional experience of leaving the planet. For looking out the window, about 15 minutes into the flight, seeing this giant, what looked like an island to me, and then all the sudden, I realized it was the continent of Africa. That had special meaning to me because I had spent a lot of time pre-flight studying the geography of Africa, so I’d be able to look down and kind of pick out the countries from where I might have descended. Only to realize, from orbit, that there are no borders or boundaries that you can see.

How did that notion of no boundaries change the way you think about people and societies?

Immensely. It changes your whole perspective on the planet and your place in it. You notice when you look down that we live on one ocean and the continents are these bodies of land that poke up in that one ocean. Humanity has named the bodies of water different “oceans,” but it’s one ocean. And you realize that, just like the atmosphere, you do something bad in one part of it, eventually, it will get to everybody.

That certainly ties into the work that Terra Alpha does.

That’s exactly what attracted me. We have to take care of the environment.

One of the favorite pastimes of astronauts is taking pictures – we call it Earth observation. So when we talk about the Amazon rainforest and its deterioration, it’s not because somebody thinks that. It’s because we’ve got the photographic documentation through the earliest days of the Apollo era to map out how we have deforested huge portions of the Amazon rainforest. Or the Aral Sea in Russia. So you see all kinds of direct signs of the impact of the environment on the planet.

How does seeing those things influence your thought about the Earth’s resiliency or fragility?

It didn’t change my thoughts about Earth’s fragility, it convinced me that the Earth would not be able to sustain our lives if we kept letting it deteriorate. It’s human beings that are fragile. The planet will still be here the way it’s done for billions of years. But we would be like the dinosaurs. So I disagree when environmentalists say that we’re going to destroy the planet. We’re going to destroy us. And I’m not sure that most people understand that slight difference. We depend on the planet. The planet doesn’t depend on us.

Why has that difference not gotten through to people?

I’ll use an example. I was listening to an interview on NPR this morning with a young couple out of North Carolina or Tennessee or somewhere who were Trump supporters. And they were explaining why they remained so and why, while they have empathy for Black Lives Matter and empathy for Black parents who worry about their kids, they don’t have anybody in their neighborhood who’s had that problem, so they’re not really sure it’s a real problem. So why should they worry about it?

The vast majority of people on the planet have never lived in a place like Calcutta, or some of the rural places in America, or Flint, Michigan, where they don’t have clean drinking water. So, particularly for people in countries like the U.S., we can’t conceive of not having water, though there are millions of people on the planet who don’t have clean drinking water. We can’t conceive of people who can’t wash their hands to prevent contracting COVID-19 because we always have water to wash our hands. I think that’s why we have a hard time convincing our fellow human beings that this stuff is important: they don’t identify with what doesn’t impact them directly.

Thinking about the notion of risk, you’ve said that commitment to service justifies risk for you.

Yes. I flew my first flight in January of 1986 – launched on the 12th, landed on the 18th. Ten days later, we lost Challenger on January 28th – with the astronaut who had inspired me to even think about applying to the space program, Ron McNair. It was devastating. It was emotionally draining. It was a shock, and it kind of made you stop and think: Why are we doing this? Should we be doing this? I think every single one of us in the astronaut office probably asked the same questions. I thought about it for about a nanosecond and realized that the reason I was there was to allow myself to represent everybody else on the planet to explore and try to find answers. It was important to not be afraid to assume that risk.