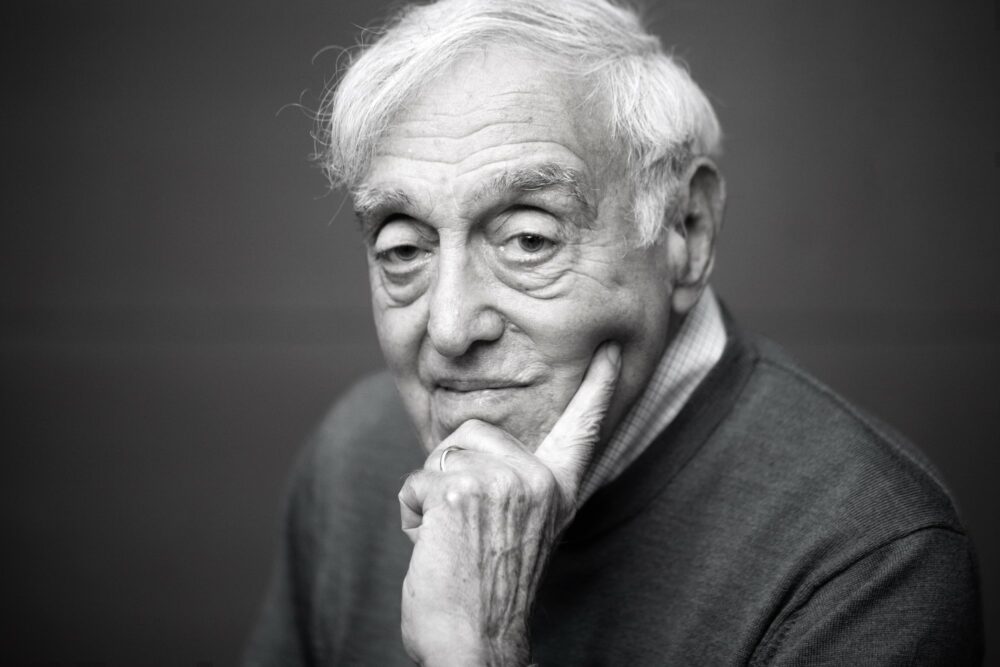

Frank Loy

Frank Loy is a diplomat, business and nonprofit executive, and attorney. He served in five Democratic administrations, having been appointed by Presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama to senior State Department posts after serving in the administrations of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. As undersecretary for global affairs in the Clinton administration, Loy’s portfolio included the environment and climate change, and he was lead U.S. climate negotiator for three years. He has been a member of Terra Alpha’s Advisory Board since 2016.

You’ve had a distinguished career working in the public and private sectors and serving on nonprofit boards – how did you first get involved in environmental issues?

My first introduction to the environment was largely prodded by my wife. She said, you know, if you’re going to do philanthropic stuff and spend time and money on organizations, you ought to know what the hell they do and whether they’re any good or not. And you really don’t know that; you’re just spreading money around a little bit and not very thoughtfully.

And so I spent some time trying to look at the environmental landscape, because it struck me as both important and intellectually fascinating. And what interested me was, unlike other philanthropic efforts, it involved science, politics, economics, and international affairs. And I liked market-based solutions like pricing and stuff like that and working with industry.

You hear environmental advocates today talk about how the Earth’s temperature is rising and how, in the not-too-distant future, it might become inhospitable to human life. Do you think the pace of change today is enough?

The pace we’re on right now is totally, totally unacceptable and totally, totally inadequate. But we, in the United States, have a problem that is interesting that I think almost no other industrialized country has. And that is that the issue has become a partisan political issue. It’s almost impossible to contemplate that this issue would divide us – not on rich/poor or on people who get dividend checks from certain corporations and those that don’t, but on political party affiliations. If you ask somebody, “Do you consider climate change a real serious problem?” you can predict reasonably well what their answer will be depending upon their educational level, their economic level, city versus rural, but by far the most effective predictor of their answer as to how serious they think it is, is their political party affiliation. That is a tragedy of absolute first order.

Having worked in the government so many years, how do you think it got to that place?

I think Republicans have a perfectly valid intellectual bedrock, and that is, they are concerned about an excessively interventionist government. I think they’re totally wrong, but that’s an intellectually credible argument. And when the issue of climate change first arose, two things were true. One, the guy that was preaching it day and night was the Democratic vice president of the United States and a Democratic candidate for president of the United States. The second thing is that many of the measures talked about in order to address it involved government regulation, government action, laws, etc. And, if you’re hostile to Democrats, and you’re hostile to those regulations, you’re going to end up being hostile to the prescription that they come forth with.

If you had everyone’s ear and could just whisper something about how to think about this issue in a way that could move us all forward, what would that be?

I would say look at British Petroleum, BP, how it is thinking and how it is acting, and compare that to American oil companies and American other companies. BP takes the position in a pretty fundamental fashion that the future of energy is going to be different than the current energy. They say: We want to be an energy company, not an oil company. And that’s true of the British, and it’s true of the French. It’s true of the Spanish, of the Italians, or a lot of oil companies.

So what is different about American companies? One is that the British, French, Italian, Spanish leaders of those companies didn’t grow up in Texas. I think if you look at the leaders of the oil industry in the United States, they sort of all went to Texas U or Texas A&M, and they all came from Lubbock, or something like that. I exaggerate, obviously. But, there’s a culture that is strong and that really makes change harder than in Europe. And the second thing is that the attitudes of the European governments on this whole issue. The attitude of the current U.S. government is so different than that of the Europeans, who not only give permission to organizations like BP to be sensible, they sort of encourage it. And we do the opposite.

What would you say are the most exciting environmental ideas you’ve come across?

Right now, I’m quite excited by the developments in the whole ESG [Environmental, Social, and Governance] movement – the question of whether the function of a corporation is to maximize returns to shareholders or something much broader than that. Milton Friedman said there’s only one fiduciary responsibility of a corporate director and officer, and that’s to maximize the returns to shareholders. And that is changing. The Business Roundtable, which consists about 150 CEOs of the largest companies in the United States, has said, we don’t believe in that Friedman theory anymore. We think that corporations have to deal with all stakeholders. That includes employees, customers, and society and the climate. That’s a big step. But, at the moment, the question is whether it’s a real step or just a talking step. We don’t know yet. But that’s a pretty exciting area.

So that area of corporate social responsibility is exciting to me. And that’s really what interested me in Terra Alpha. Because I certainly have had the experience where I served on an endowment or investment committee of an organization I was involved with and we wanted to do the right thing. So we took 5 or 10% of our portfolio, and we invested it in solar and batteries and other good stuff. And then, when somebody asked, well, what about that other 90%, what are we doing with that, the answer was, well, just put that in the market. And Tim [Dunn]’s genius was to say, there’s a way of handling the investment of that 90% that is better than worse. And those companies that do that better should do better. That we ought to put that together.

Do you feel like that word is getting out and might transform some of those verbal commitments?

I think much of it still is talk. But, talk has to come first, and then action has to follow. The Friedman theory about the responsibility to a corporation is, I think, at an end. So that’s changing. Now, how big the change is, how quick the change is, how far-reaching the change is, all of that’s still open.

—

Terra Alpha Voices highlights thought leaders who inform our investment process and impact work. This series, created in partnership with author and photographer KK Ottesen, seeks to shed light on the subjects’ diverse perspectives rather than their illustrious careers.